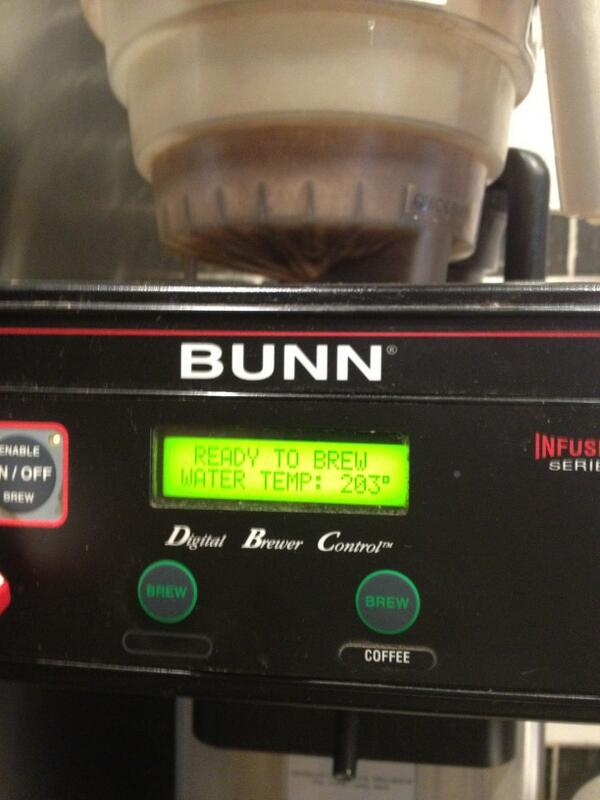

Ready to brew (h/t Ted Frank)

Because the twenty-year-old Stella Liebeck case is getting another round of attention on some blogs — Susan Saladoff’s short film Hot Coffee having served quite successfully to keep the trial lawyers’ side of the controversy in circulation — it’s worth a closer look at the latest in Jim Dedman’s (Abnormal Use) writings deflating the case’s mythos [Defense Research Institute DRI Today, previously briefly noted in a roundup a couple of weeks ago]. Excerpt:

The central issue was whether hot coffee, which by its very nature is hot, is an unreasonably dangerous and defective product because of its temperature. More specifically, the case concerned whether coffee served at 180-190 degrees is so hot that it makes the coffee itself unreasonably dangerous and defective. Shortly after the trial, The Wall Street Journal reported that McDonalds’ internal manuals at the time–produced in the litigation— indicated that “its coffee must be brewed at 195 to 205 degrees and held at 180 to 190 degrees for optimal taste.” … Contemporary media reports suggested that the coffee was approximately 165 to 170 degrees at the time of the spill, indicating that it had cooled somewhat between the time it was served and the time it had spilled….

Interestingly, today, on its website, the National Coffee Association advises that “[y]our brewer should maintain a water temperature between 195–205 degrees Fahrenheit for optimal extraction” and that “[i]f it will be a few minutes before it will be served, the temperature should be maintained at 180–185 degrees Fahrenheit.” Even in 1994, the National Coffee Association confirmed that McDonalds’ serving temperatures were within industry guidelines (and many restaurateurs have found that their customers complain if they lower the temperature of their coffee).

Failure to warn was also one of the theories in the case:

Curiously, the warnings issue receives little attention these days. Although Liebeck alleged that “the container that it was sold in had no warnings, or had a lack of warnings,” the very cup at issue is prominently displayed—with its “Plaintiff’s Exhibit 44” sticker still affixed—on both the website and the promotional poster of the Hot Coffee film. However, in the very same pictures, it is clear that the cup advises in orange text: “Caution: Contents Hot.”

Earlier coverage here, etc., etc., as well as by Nick Farr at Abnormal Use and Ted Frank at Point of Law. (Yet more: index of Abnormal Use posts).

P.S. It might be added that those “everything you know about the Stella Liebeck case is wrong” internet memes are very often wrong themselves. In particular:

* The story got onto national wires via the AP and immediately set off widespread public discussion on the strength of its own inherent interest, with no evident push from any interest group. When an organized public relations effort did emerge in early weeks of discussion, it was from the plaintiff’s side, which held a press conference in Washington seeking (successfully) to establish and solidify themes in Liebeck’s favor, such as that there had been many earlier consumer complaints about McDonald’s coffee temperature.

* The most gripping supposed “myths of the Liebeck case” were not in fact widely asserted or circulated either at that time or since. Very few commentators erroneously asserted that Liebeck had been driving or that her car was moving, or (even worse) mistakenly claimed that her injuries were somehow minor. Only by treating stray outliers as somehow representative of public discussion can revisionists portray the public’s grasp of the case as grossly ill-informed. It was then and is now plausible for both laypersons and experienced lawyers to fully and accurately grasp the facts of the Liebeck case and, based on that understanding, sharply disagree with the New Mexico jury’s verdict in her favor. That’s one reason most American juries both before and since 1994, asked to decide hot-beverage lawsuits based on similar fact patterns and claims, have decided for the defense even where serious injuries might engage sympathy for a plaintiff’s situation.

* Meanwhile, some truly extraordinary myths and misconceptions — such as that McDonald’s somehow mysteriously “superheated” its brewing water to temperatures unknown in home teakettle use — have widely circulated on the internet in years since, advanced by lawyers and even professors who have every reason to know better. Peculiar assertions of this sort seldom get attention in the oft-seen “myths of the Liebeck case” internet genre.

17 Comments

Perhaps a better name for the case would have been: Hot v. Scalding

Or even better common sense v. no sense.

Attempting to hold and balance a paper cup of hot liquid between one’s sweat pants covered knees strikes me as a feat that most circus performers would fail to accomplish. Particularly since she had a young, virile man relative less than two feet away.

I’ve heard a number of people giving informal opinions on this case. One person suggested that the coffee was extra hot because McDonald’s wanted it undrinkably hot for a few minutes so homeless coffee purchasers would not stay and drink it. I’ve heard others suggest the coffee cup itself was defective and the heat of the coffee melted the bottom and/or sides.

Of course, the documentary Hot Coffee doesn’t really have any argument other than “look how bad she was hurt!” and “some people sustain terrible injuries!” Both of which are tragic, even gruesome, but don’t address the question of who is liability when for how much. That sounds a lot more like insurance, as though a coffee seller must bundle catastrophic coffee-spillage insurance with each cup sold.

It’s horrible when someone is injured so grievously, but the jury scaled the award to the amount of coffee McDonald’s would sell in a given morning. That doesn’t sound like insurance, which would be relative to the injury sustained. That award sounds punitive, like the coffee seller did something wrong and must disgorge some of the profits from that bad act. So at once this is an implied strict liability (you sold coffee to somebody hurt by the coffee) without any need for culpability, but the scale of judgment is punitive for wrongful actions (you wrongly sold hot coffee for profit). The juxtaposition serves the interests of plaintiffs litigators, since it’s easier to sue and easier to get big awards, but it doesn’t make any kind of legal or policy sense.

Turk,

Coffee v. Lap

“Superheated water”. The only way to do that is to keep it under pressure. Only problem is that as soon as the pressure is reduced the temperature comes down or the water turns to steam. This is what you get when our schools teach “environmental science” instead of things like Physics and Chemistry.

I understand that Ms. Liebeck was taken to a hospital after the spill, and she was cared for. When she got the bill from the hospital, she asked McDonalds’ to help pay her pay it. Clearly the company had no duty to help her, and may have been barred by business law from accepting an unwarranted liability. Ms. Liebeck’s lawyer, the jury and society trashed the concept of rule of law to force a third party to be charitable. But nobody analyzed whether her care was excessive or the hospital bill was bloated. I suspect that was the case. Our moronic journalism probably missed the real story here.

The ideal brewing temperature for coffee is just under 200F. Serious coffee drinkers will pour coffee brewed under 190F down the sink.

It takes 5 seconds for water at 140F to cause 3rd degree burns. That is why I set my hot water tank in the basement at 135 and no higher.

It takes 1 second for water at 155F to cause 3rd degree burns.

Be careful.

This was a horrible freak accident. Nobody did anything wrong. McDonald’s has served tens of billions of cups of coffee. Several one in a billion accidents would be expected to have happened and one in 10 million accidents number in the dozens per year. The list of products comparably dangerous to McDonald’s coffee is long and includes jeans (zipper injuries, really) and nachos (even more dangerous, and served to children at parks around the country every day).

[…] it pops up this week via postings at Abnormal Use and Overlawyered, among other places, claiming there are myths that need debunking, as if 20 years of analysis […]

Why are we sitting lay juries in civil trials? It’s in many state constitutions, I know, but what’s the policy rationale? Serious question here. I’ll admit that in most cases juries are, as the post suggests, capable of grasping both the facts and the law, but isn’t it also possible that the mere chance that a jury can be swayed by emotional appeals employed by an adept plaintiff’s attorney (particularly in certain jurisdictions, with certain plaintiffs and/or with certain injuries) driving much marginal litigation? The fact that the judge often has the power to overturn the jury verdict afterwards, or to reduce a high award, makes it seem even less useful.

As for the Liebeck case in particular, although the public generally appears to agree that the outcome was unjust, blame is usually cast on either trial lawyers or the plaintiff herself, rather than on the jury that entered the verdict. Tort reform efforts seem to reflect that mindset.

Why are we sitting lay juries in civil trials? It’s in many state constitutions, I know, but what’s the policy rationale?

In England, it was King George III that was the sovereign.

When we broke from England, the Founders wanted to make sure that power resided in the citizens, not a head of state. Thus, the Bill of Rights.

Three of the amendments set forth explicitly that it is the community (a jury) that retains power:

5th Amend (Grand Jury)

6th Amend (Criminal trial by jury)

7th Amend (Civil trial by jury)

That distrust of government that existed at the time of the Revolution still exists today, as can be seen in many political movements.

Thanks Turk – I kinda get the justification for the provisions in the Fifth and Sixth Amendments, as they related to criminal prosecutions where it is a citizen facing the state. But a civil trial is citizen v. citizen. The state is usually not a party. Why is it necessary that the fact-finding power rest in a jury rather than in the judge, a guy whose occupation is adjudicating disputes? I guess I’m struggling to see what “distrust of the government” has to do with litigating a personal injury claim in state court.

Why is it necessary that the fact-finding power rest in a jury rather than in the judge…

I presume, without going to look in the Federalist Papers, to stop judges from becoming too powerful. There are plenty of litigants with very significant interests that appear in courts.

And I do find it odd that some people think a judge would be any better at deciding who is telling the truth on the witness stand and who isn’t.

Judges have biases also, you know. Remember that, to become a judge, you have to know the right people, regardless of whether the position is an appointment or s/he needs go get onto a ballot through a political party.

[…] still making news. Just this week, stories about this case have appeared at blogs Abnormal Use, Overlawyered, and the New York Personal Injury Law Blog. Ezra Klein wrote about the case just yesterday on […]

I presume, without going to look in the Federalist Papers, to stop judges from becoming too powerful.

That’s the only reason think I could think of, too, except that fact-finding is a relatively modest part of the full range of judicial authority (the power is given only to the trial courts), and is irrelevant in many cases where the essential facts aren’t disputed, or the challenge itself solely concerns a legal, rather than factual, issue. Far and away the more powerful role, in civil cases, is being able to say what the law is, whether that is the power to mold the common law in a negligence case or the power to strike down an entire statute as unconstitutional. Next to that power, fact-finding seems pretty routine and unexceptional.

And I do find it odd that some people think a judge would be any better at deciding who is telling the truth on the witness stand and who isn’t.

I’m not one of those people. A judge may have heard a lot more testimony, on the one hand, but juries have strength in numbers on the other. The advantage isn’t clear, which to me weakens the case for a civil jury as a constitutional right. If it’s not about government power, and juries aren’t clearly better fact-finders than judges, why go through all the bother of time, expense, missed work, disruption, etc. of hauling in jurors?

I agree that judges have biases, too, but there is a system for recusal where interests are too closely linked. And a system of appeals to panels of judges, who can overturn clearly erroneous factual findings or order new trials. Not to mention that the “bias” argument could apply equally to questions of law as to questions of fact, but we don’t argue for turning legal analysis over to the jury on that ground.

@Robert:

That’s the only reason think I could think of, too, except that fact-finding is a relatively modest part of the full range of judicial authority (the power is given only to the trial courts)…

First, while you say fact finding is a relatively modest part, others may say it is the most important part. It depends on the case. It matters 100% of the time when the facts are in dispute.

Second, you wrote that the power of fact-finding is only given to trial courts. But that is not the way the Constitution was written:

Article III, section 2:

In all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party, the supreme Court shall have original Jurisdiction. In all the other Cases before mentioned, the supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction, both as to Law and Fact, with such Exceptions, and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make.

Amendment Seven would limit that previously given constitutional power (“…and no fact tried by a jury, shall be otherwise re-examined in any Court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law.”).

We return, in essence, to the concept of the citizenry being the sovereign and not the king (We The People…).

Last: Some people have tried to do studies of the differences between judges and juries (such as, for example, having judges write down what their verdict would be, for purposes of the study only, had there been no jury).

You can find a little round-up of the studies, for what they are worth, at this Slate article:

http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/explainer/2013/07/zimmerman_trial_how_accurate_are_juries.html

Thanks for that link, Turk. Very interesting and relevant, but the studies cited only looked at criminal trials, rather than civil trials. Obviously the concept of “acquitting” or “convicting” doesn’t quite apply in the civil context, and the notion (if we can postulate from the statistics cited) that judges, being state employees themselves, may in some cases be subtly biased toward the state prosecutor, would not apply in a dispute between two private parties.

There’s a mention of jury nullification in there too, but again that doesn’t really apply in the civil context. Or, on the other hand, the outcome in Liebeck could be viewed as a form of civil jury nullification — of a jury overriding legal and public policy principles to award damages to a sympathetic plaintiff. Here’s one of a very few studies in this area citing similar concerns to mine:

“Concerns about protecting citizens against oppressive government action do not arise in lawsuits between private parties. Beneficiaries of nullification may applaud the jury’s function in softening the application of seemingly harsh rules, but their adversaries will voice legitimate complaints that nullification sacrifices their due process rights. In addition, when a jury chooses to disregard laws adopted by legislatures or courts, it undemocratically usurps the lawmaking function lodged in those institutions. Thus, courts should more readily embrace tools such as special verdicts and bifurcation of trials in order to minimize the risks that civil juries will deviate from their instructions.”

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=266961

Much of the outrage over the Liebeck case, to me, seems to stem from a sense that perceived nullification in a civil context, rather than being an instance of people standing up to the government, actually represents a miscarriage of justice, although the in civil cases the presence and role of a jury seems to attract very little attention as compared to criminal trials.