Elizabeth Mullaney Nicol has an excellent article in The New Atlantis on the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act and its appalling consequences for old children’s books and the cultural inheritance they represent. (If you’re new to this topic, we’ve covered it extensively here and here.) Among the questions she addresses:

Elizabeth Mullaney Nicol has an excellent article in The New Atlantis on the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act and its appalling consequences for old children’s books and the cultural inheritance they represent. (If you’re new to this topic, we’ve covered it extensively here and here.) Among the questions she addresses:

Isn’t there a wealth of worthwhile children’s literature published since 1985 for kids to read?

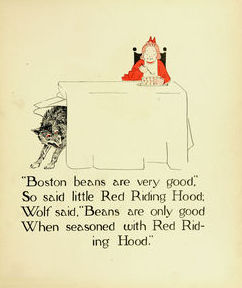

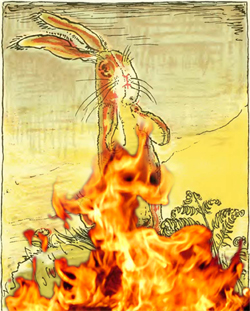

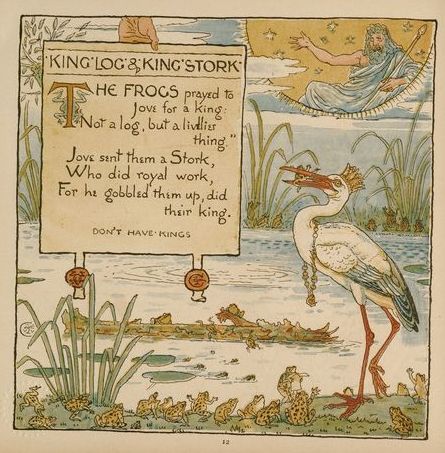

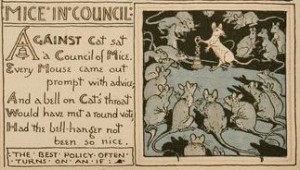

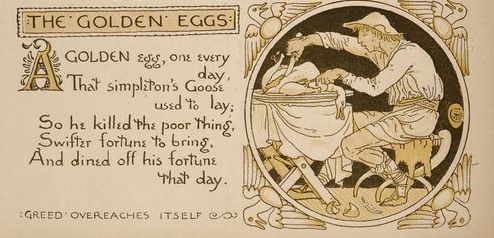

[Older books,] as a group, have certain desirable characteristics. Children’s books of yore tend to use more sophisticated, literary language than their more recent counterparts. The quality of their paper, bindings, and illustrations are often superior. Vintage children’s books assume and encourage the readers’ fascination with adventure, their eagerness to learn about the world, their respect for great men and women.

Won’t the really good older books survive in post-1985 reprint editions that can be sold without fear of liability? (Yes, one really does hear this argument.)

Some books from the 1950s and 60s are back in print, but with updated illustrations so the characters appear to be from our time; if that’s what it takes to lure readers who are wary of anyone who doesn’t look like them to pick up the books, it’s probably fine, but there is also value in presenting books with a style of illustration and characters with a style of dress from a different time, and that’s what we get with old copies. Some books, such as the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew series, are thoroughly “updated” for today’s readers—simplified, abbreviated, substituting familiar words for those no longer commonly used—so if a child is going to read the originals he needs to read old copies….

Some old books, it is true, express ideas and attitudes of which we would disapprove, prejudices and errors that make modern readers wince. But learning about such sentiments firsthand is at the heart of what it means to learn our history. Moreover, while correcting some of these past problems, our present age has its own objectionable attitudes.

Won’t older children’s books still be available when intended for adult use, say as collectibles or for research?

But the availability of these books to children is the very purpose and value of preserving them. We want them in children’s hands, being read, not only preserved on the dusty back shelves of research libraries. Quantities are important — quantities of titles, and quantities of each title, so they are readily available for loan from public libraries and for purchase through used booksellers. Families have been able to build home libraries through priced-for-reading book sales and thrift stores. … We are suddenly facing the prospect that many of these books will be destroyed, making those that remain all the more rare and inaccessible.

Some used booksellers, trying valiantly to continue selling books for children, are re-labeling their children’s books as collectors’ editions. But this obscures the books from searches by those looking for ordinary children’s books, it clutters the market for real collectibles, it makes the bookseller look ignorant of his trade, and it is prohibited under CPSIA, which stipulates that a book “commonly recognized” as being meant for children’s use will be regulated as such.

The article’s strength, I should note by way of quibble, is not as legal advice: it somewhat overstates the stringency of the law, which does not ban the sale of all untested pre-1985 kids’ books as such, instead exposing booksellers to punishment when they guess wrong about whether a given volume would meet current standards (hence the CPSC’s guidance advising retailers to discard them all). And the call for “sequestering” library copies has thus far come from only one member of the three-member CPSC, not as yet the full commission. As a summation of what will be lost to children and the nation if Congress does not change this law, however, the article is one of the best yet. Read it here.

Relatedly, Ken at Popehat is still trying to grasp the news that according to our federal government:

Children’s books have limited useful life (approx 20 years)

And since Rep. Henry Waxman, closely identified with CPSIA and its defense, has a new book out, Carter Wood at ShopFloor wonders whether this topic is going to come up at any of his bookstore appearances.

P.S. Fenris Lorsrai at LiveJournal reprinted the Nicol article and in so doing prompted some interesting reader comments.

GRAPHICS courtesy VintageChildrensBooks.com.

Filed under: CPSIA, CPSIA and books, CPSIA and libraries, Henry Waxman

had an op-ed in the Journal last week on the continuing damage being wrought by the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act (CPSIA). Related: Rick Woldenberg (“Big Toy may be prospering right now, but the little guy is getting killed”). And Karen Raugust at Publisher’s Weekly has a year-end status report on the unpleasant effects of the law on various segments of the kids’ book business, including retailers, “book-plus” and novelty book makers, and one of the most seriously endangered groups, sellers of vintage children’s books.

had an op-ed in the Journal last week on the continuing damage being wrought by the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act (CPSIA). Related: Rick Woldenberg (“Big Toy may be prospering right now, but the little guy is getting killed”). And Karen Raugust at Publisher’s Weekly has a year-end status report on the unpleasant effects of the law on various segments of the kids’ book business, including retailers, “book-plus” and novelty book makers, and one of the most seriously endangered groups, sellers of vintage children’s books.

However, the CPSC has yet to issue promised guidance to libraries on pre-1985 books:

However, the CPSC has yet to issue promised guidance to libraries on pre-1985 books: Elizabeth Mullaney Nicol has an

Elizabeth Mullaney Nicol has an

President Obama has nominated South Carolina lawyer and former schools commissioner

President Obama has nominated South Carolina lawyer and former schools commissioner

This may have been good advice, but I was still a little surprised.

This may have been good advice, but I was still a little surprised.